The War of Words

In this Adventures in Odyssey drama, a carelessly uttered word from Eugene creates havoc as it becomes the fashionable insult, resulting in a lesson about the power of words.

Home » Episodes » Focus on the Family Broadcast » Leading Your Child Through Emotional Milestones (Part 2 of 2)

Excerpt:

David Thomas: Parents are so quick to want to go to, “I want my kids to figure out how not to melt down. I want them to figure out how to work through frustration better.” And that’s an important objective. But if they don’t even know what they’re feeling, like, that’s the foundational building block. That’s why we start with vocabulary. We’ve got to figure out, “What is it that I’m feeling so that I can then figure out what to do with it?”

End of Excerpt

John Fuller: David Thomas is with us again along with his co-author and co-worker Sissy Goff. And they’re going to share more about emotional milestones in your children. I’m John Fuller, and your host today on Focus on the Family is Focus president and author Jim Daly.

Jim Daly: Hey, John, it’s so great to have Sissy and David with us and back with us today. Last time, we covered some, I think, really incredible insights. And I’m hoping for you, the listener, I’m asking the questions you want me to ask. That’s my goal as I sit here thinking of the content, even out of my own experience as a father and Jean as a mother, you know, the things that we’re struggling with. And that really is all to help you be a better parent and do the job God’s called you to do. You know, sometimes it’s a little daunting to think that He has only loaned us the kids, right? And then, man, they’re gone. And we’re on the precipice of that. We have one of our boys who’s gonna be a senior and our other one’s a sophomore. We’re not far away from the empty nest. You’ve gone through that, John. You’ve had four of the six…

John: Some of that, not the empty part. But yes.

(LAUGHTER)

John: Several kids have launched and gotten out.

Jim: You’ve launched some of kids so – I mean, that’s a big moment when they’re, like, now adult peers, right?

John: When you say goodbye and you realize they’re not gonna be coming back and staying with me anymore…

Jim: In the same way.

John: …At least not the same way, it’s a pretty big deal.

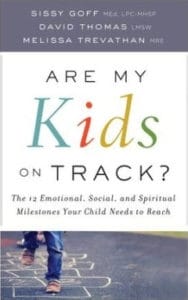

Jim: That’s true. And I hope if you didn’t catch the program last time, get the download. Call us and get a CD or maybe even get the smartphone app. And you can listen that way as well. But there’s lots of ways that you can listen. And this is our purpose. Man, we want to help you be the best mom and dad you can be. And the resources that we cover on the program – that’s our sole intent. And today we’re gonna cover more of the great content from Sissy and David – their book, Are My Kids on Track?

John: Yeah. And Sissy is the director of child and adolescent counseling. David is the director of family counseling. Both work at Daystar Counseling Ministries in Nashville, Tennessee. And this book is available along with the CD, the smartphone app and other help, including a feelings chart that we mentioned last time at focusonthefamily.com/radio.

Jim: John, how are you feeling today? Are you happy, sad, angry?

John: I’d rather not talk about it, Jim. I haven’t hit my milestone.

Jim: I think you’ve answered the question right there. David and Sissy, welcome back.

Sissy Goff: Thank you. We’re so glad to be back.

David: Thank you.

Jim: Now David Thomas, you’re not the guy that invented the Wendy’s hamburger?

David: I wish I had access to that inheritance.

(LAUGHTER)

Jim: I just wanna clarify.

David: No connection.

Jim: We ended last time talking about, you know, the impact of a dad on the daughter. We talked about boys and how they respond to mom and some of those basic things, identifying the stumbling blocks, as you call them. And Sissy, you talked about control of a little girl, what she’s developing there – kind of the insecurities of that, wanting to be perfect, that idea of perfection. And again, if you missed that, get it. I want to come back to that briefly on the anxiety side. And this can be both a mom or a dad. But when you see anxiety in a child, what do you normally see in the parent?

Sissy: Well, there’s a lot of research that says anxiety is a childhood epidemic in America today. I think from our counseling offices, we would say anxiety is a parenting epidemic in America today.

Jim: Is a parenting epidemic – it’s parents who are the ones who are anxious. And we’re transferring it to our kids?

Sissy: Yes. Yes. And some of it, I think, is really overcompensating – that I think we all are kind of near the same age. And we grew up in a generation where we weren’t talking about our feelings. And our parents weren’t often asking us about our feelings. And so maybe we had anxiety, and no one ever knew. And so we’re seeing parents who are over talking with their kids and really trying to step in and fix it, like you said. And basically, what experts will say is with anxiety, to work through it, the child just has to do the scary thing. And so when we don’t let them, we’re, in effect, preventing them from working through it. But they need to do it in a gradual way. But they still got to do it.

Jim: Sure. Give me a handle. I’m a mom or dad – David, you can jump in on the dad’s side here. What does that handle for a quick self-assessment that I’m dipping toward anxiety? How do I see it in myself with my child? What would be some of those experiences – if you’re doing this, then you may be informing your child in an unhealthy way?

Sissy: Are you doing it for them or are you stepping in and removing whatever is causing the anxiety in the first place? If it’s track, are you letting her quit the track team immediately without pushing through and having to work through it a little harder?

Jim: Doing the homework.

Sissy: Doing the homework – going to school – I had a family recently who – a lot of kids have some school refusal where they’re worried about going to school. And there are ways that you can help them work through that without just pulling them. And I saw a family who had completely pulled their daughter from school. And by the time I got with her, it was obvious she was in complete control of her house. And that’s part of it – is they’ve got to know that we’re bigger. That makes them feel safe like we talked about.

Jim: David, what about boys in that same way? Do they suffer from some insecurity?

David: Oh, absolutely they do. And I was even thinking, when you were asking that question about parents, where I mentioned earlier with boys, I’ll do a lot of training around listening to your body and figuring out when your body’s signaling an alarm. And I have to do a lot of that with parents. Like, we laugh about how often we’ll have parents in our office who will say things like, “He’s so worried, and I don’t know where that comes from.” And you’re thinking…

(LAUGHTER)

Sissy: Feels palpable in you.

David: …Really? I’ve challenged parents, hopefully in a respectful way, to just say, like, “Are you aware even right now? Like, your voice is elevated. Your hands are clenched at this point. You’re yelling as we talk. Like, not listening to the signals your own body is giving you in this moment.”

Jim: Well, and I think that’s the reason for my question, is that our self-awareness can be really diminished in this area of parenting ‘cause it’s so close in. We’re gonna be far more self-aware in a social setting, in a workplace. But at home, we’re kind of just who we are. That’s where we’re relaxing, at – at least in terms of facades.

Sissy: We talk a lot…

Jim: Is that fair?

Sissy: We talk a lot in the book about parenting out of love and not out of fear. And that’s kind of the bottom line in that.

Jim: Yeah. That is so true. And I think the key thing there is – what I’m tryin’ to pull out of ya is how does a parent do a quick self-assessment that “I am a fear-based parent, and I’ve gotta change?” And I know there’s no quick way to do that. But I’m just thinkin’ of the poor mom or the poor dad listening who is saying, “Okay, I think I do parent out of fear.” How do we confirm that for them? What would you say?

David: In the chapter on awareness, we do talk with parents about the importance of not only knowing your stuff, checking your baggage, but talking openly – obviously age-appropriately – with our kids too, to be able to say things to them like, “You know what? I have a tendency to bend toward catastrophic thinking.”

(LAUGHTER)

“That’s kinda where I go. I go quickly to worst-case scenarios.” And so being able to say those things, tell on ourselves in that way, and understanding what do I need in response to that. Like, we’ve talked about empathy and questions and coffee in case of the third kinda magic equation we talk a lot with parents about – it’s time and space, and to be able to say to the kids we love, “You know what? I’m amped up right now. Like, I’m flooded with worry right now. Like, in this moment, I don’t feel like I’m in my” – I – with boys, I call it your dinosaur brain or your thinking brain, you know, your emotional brain, your thinking brain – for us as parents to be able to say, “I’m not in my thinking brain right now. I love you too much to argue, so I’m gonna go take 15 minutes to walk the dog, do whatever I need to do at this point. And then we’ll come back together and talk so that I’m not parenting out of fear, so that I’m not parenting out of emotion.” When we’re emotionally charged, kids or adults, in those moments, it’s like what happens when I go to the grocery store on an empty stomach. I just – I don’t make thoughtful decisions.

Jim: Let’s move to empathy. Talk about the importance of empathy, what empathy is and teaching your child how to, um, express empathy. It’s kind of a big question there, but either one of you, just kick it off.

David: Maybe a short definition would be if vocabulary – the milestone of vocabulary is reading emotions, empathy is responding to emotions. So it’s the ability to kind of look at you and have some sense of what’s going on inside of you, climb into your shoes. And we know – there’s so much research out there that continues to confirm that empathy is one of the most foundational ingredients in healthy interpersonal relationships of all kinds – marriage relationships, parent to child, coworker relationships. So we don’t really need to have much of any conversation about whether we think it’s important or useful. It is, no doubt about it. And the research continues to confirm it.

So kinda where we go in the empathy chapter and every chapter is breaking down what are the stumbling blocks for boys, what are the stumbling blocks for girls, what are the building blocks for boys, building blocks for girls? And then at the end of every chapter is 10 practical, easy, user-friendly ways that a parent can be doing this in your home every day.

Jim: Well, let’s go with the boys. What are the stumbling blocks? And then what are those, uh, antidotes to help them?

David: Oftentimes with boys the first and biggest is gonna be awareness. Like, where he has trouble reading his own emotions…

Jim: That’s pretty true.

David: …It’s all the more difficult to read it on others. And so one of the practices I recommend for parents is doing a lot of people studies. You know, if you’re just sitting in a – a…

Jim: Airport.

David: …Restaurant airport, and like, “What do you think that guy over there is feeling? What do you think’s going on? He’s talking on the phone.” Having him be able to look and put some of those puzzle pieces together, using movies, hitting pause at different points on the way when we’re watching movies or reading books with kids and kind of doing a little dissecting in those moments is a useful practice with a lot of boys.

Jim: Yeah. If you have an older child now, and you’re feeling – I mean, I’m – I’m not even sure what a red flag would look like if they’re not empathizing. Uh, give me an example, a practical example, where you have a 15, 16-year-old, and you should be – the alarm bells should be going off. What would that look like, and then what can you do?

David: Well, one of the first things we would say, I think for boys and for girls, uh, with adolescents – and this is a part of where just letting development serve as a backdrop is so important – that we acknowledge one of the things that’s at play with every adolescent is they’re thinking more about themselves than others.

Jim: Yeah. At 5, 6, 7, that’s kinda normal, right?

David: Oh, absolutely.

Jim: It’s hard to raise a child up at that age to say, “Be empathetic.”

Sissy: And it’s normal at 15, 16, 17. We could add a one to each of those numbers too.

(LAUGHTER)

David: Yes, yes.

Jim: Well, I would hope – I hope that they would have more coping skill at that point, more ability to be able to do that.

David: They would. But what could get in the way is that reality of, “I’m thinking so much about myself, and I’m insecure and unsteady inside of myself, that I can’t be as aware of you. It’s not that I don’t want to or have the skills to, but I’m so road blocked by adolescence in those moments.” So…

John: And that – that’s like, “My complexion is bad, or I don’t stand out the way I want to, I stand out in a bad way, so I can’t even get outside of that.”

David: Yes. And – and there’s – you know, for years developmental psychologists have called one of the things that happens in adolescence the imaginary audience, this phenomena that kids are believing in all moments, I’m being observed, critiqued, watched, talked about. And that…

Jim: It’s pretty much true.

David: Yeah.

Sissy: And now more than ever ‘cause this is…

David: Social media has confirmed that to be the case. And so kids are so consumed with that they can’t be aware of others in ways that they’ll have the capacity to do differently, say, for example, in their 20s. And – and that feels so foundational to us to talk about and understand because in those moments – you mentioned this earlier – a parent could easily go to a place of just thinkin’, “Oh, my goodness. He’s 16, and he doesn’t have any evidence of empathy.” And I would always push back on that, and to say, “He’s 16 and likely doesn’t have a lot of evidence in some moments.” But requiring him to be in situations, something as simple as an elderly neighbor on our street lost a spouse, so let’s write a note to that person and take it – you found out – my sons at 15 just found out their beloved soccer coach lost his mom. And I’m like, “Let’s write him a note at this point and practice, roleplay having a conversation.” A 15-year-old boy doesn’t know naturally how to approach a coach they love and respect and acknowledge that he lost someone he loves.

Jim: And that’s what…

David: So that’s – that’s something we have to practice…

Jim: And that’s…

David: …No different than riding a bike.

Jim: …What you call a building block?

David: It is.

Jim: And I – you know, that’s really interesting to think of it that way ‘cause I think sometimes as parents, we look at that, and of course you should know what that means. You should be empathetic. And then we get – uh, you know, we lack, uh, patience with that child that they don’t know how to react. But we’ve gotta teach ‘em how to react.

David: We do.

Jim: That’s a great point.

David: We do. I – I remember when one of my sons was in sixth grade, he came home and was aware that one of his best buddies’ parents were going through a really hard, high-conflict divorce. And he said, “Dad, I wanna check on him. But I’m worried if I ask him about it at school, it’ll make him too sad. And I’m worried if I don’t ask him, he’ll think I don’t care.” And don’t we all know that tension as grown-ups?

John: What a great question for him to ask you.

David: And that’s a great example. He didn’t instinctively know how to ask the right amount. And so we’ve gotta practice those kinds of conversations with kids so they can develop empathy.

Jim: Well, and I love that that – the way that you’ve built the book, with those stumbling blocks and then building blocks. Uh, Sissy, let’s go to the girl’s side of empathy. Um…

Sissy: I was about to say, on the flip side of David’s story, I had a girl that I was working with who was a seventh grader – because girls just inherently, I think, have more empathy from their earliest stages, but they lose it in adolescence. And she said to me, “My best friend and I are so close. We talk about everything. We share everything. I think her parents got divorced last year, but I’m not really sure.” So…

(LAUGHTER)

Sissy: …Great picture of a total lack of empathy in her adolescence. But that’s really normal for her too.

Jim: Oh, that’s interesting.

John: It is, and our guests Sissy Goff and David Thomas have a great book. It’s called, Are My Kids on Track? Get your copy and a download or a CD of this broadcast at focusonthefamily.com/radio, or call us if you have questions or just need some encouragement. Our number here is 800, the letter A and the word FAMILY.

Jim: Sissy, I’m not gonna let you off the hook that easy when it comes to the girls, though, because in the book you talk at length about narcissism. And I always think that – of that as an adult feature ‘cause you’ve lived enough life, you disregard people. The whole universe is about you. And it takes a little time to get there, I thought. But you – you subscribe narcissism to young girls, that it’s a – a normal growth pattern. Tell me what – what you’re driving at with narcissism.

Sissy: Well, I think it starts typically around the age of 11, when they’re – when puberty kicks in. But now we have girls who are starting their periods as young as 8, so you can see strains of it earlier on. And it – typically, by about junior year they’re cycling out of it, which is the great news. But all girls are narcissistic to some degree like David talked about. They’re thinking about themselves perpetually, and they’re thinking about what other people are thinking about them. And so social media has made that significantly worse because it’s in their face all of the time. And so with girls, I think we want to continue to remind them of who they are in terms of caring that they’re thoughtful of other people, that they – that relationships matter to them. We wanna give them opportunities to grow those skills in every way possible. And I think, again, because girls are empathetic more naturally just with their – who God’s made them to be and that difference like we talked about, one of the things that we really look at is, I think, with all of us, we have this language that’s happening verbally. But with girls, there’s this sublanguage that goes on that’s nonverbal, that’s kind of this undercurrent. And when girls start to miss that, we become concerned that there’s something more going on, such as ADHD, anxiety. Those are two things that make them start to miss social cues. And so they lag behind even farther, and those girls are gonna have a harder time developing empathy a lot of times.

Jim: Yeah. And in – in that context, you’re wanting to develop awareness and humility within the – how does a parent go about developing humility? I mean, I – I got a couple of ideas.

(LAUGHTER)

But they may be the most appropriate. But…

Sissy: Well…

Jim: …You’ve got to be, uh, kind of mindful of how to do that, um, not draconian.

Sissy: Well, and again, I think because girls by nature want to offer something of themselves, they want to care about other people – they have more oxytocins flooding their brains, which is the nurturing hormone – and so how do we get them in places developmentally where they are serving? I think that’s really a bottom line. And so taking them to a soup kitchen to help serve, taking them on mission trips. And again, with that narcissistic adolescent thing they got going on, those years especially are important for them to be often even having experiences away from home, away from their parents, where they get to feel like they’re making a difference. Because that’s one of the places we get most concerned about kids anyway when we talk about depression, is those kids start to believe they don’t matter. And so how can we give kids an opportunity at each stage developmentally to feel like, “I really do make a difference in the life of somebody else? And when it doesn’t come naturally to me.”

Jim: Well, and that’s so good in the book. For the parent of a seventh, eighth, ninth grader, I mean, again, these are phases. Your kids are going to go through difficult moments. Some of it’s gonna be hormonal. And to better understand it is critical so you’re not freaking out as a mom and dad, saying, “Oh my goodness. We have an axe murderer.” No. This is just…

Sissy: Or narcissistic personality disorder growin’ in our house.

Jim: Yeah. That – that would not be good either.

Sissy: No.

Jim: But it’s being mindful of it and taking the long view and understanding where you’re at. Um, David, let’s go to the – that boy, maybe that little boy, and they’re expressing, uh, blame or avoidance or denial, kind of the stumbling blocks for that little boy when it comes to resourcefulness. What is resourcefulness, and what do those stumbling blocks look like?

David: Resourcefulness is really taking the emotion to something constructive. It’s problem-solving. It’s strategizing. It’s critical thinking. And it’s kinda part of that two-part agenda we talked about earlier, figuring out what do I feel, and then what to do with it. It’s the what-to-do-with-it part. And – and boys, I love helping boys develop in this area because I think, again, as males, we’re kinda a natural problem-solvers. So this is flexing a little stronger muscle. But the three stumbling blocks you mentioned are kinda his biggest roadblocks of Blame, Avoidance and Denial. I have that acronym of BAD in the book because I think boys do a lot of, in the face of failure or in the face of, you know, difficulty, swinging between blame and self-hatred, somewhere between “It’s your fault” and “I’m an idiot.” And they have a hard time getting to that good, healthy middle space. Like, I had a conversation with an 11-year-old boy just yesterday in my office. And he struck out three times in the same baseball game. And he was talking his way through it. And the things I heard from him were those two extremes. Like, the pitcher couldn’t even throw the ball – there’s blame. And then he got to at some point, in a teary moment, “I’m the worst player on the team.” But nowhere in the middle was the sense of, “I had an off day,” or “I missed practice one day this week and I was a little bit, you know, not as in my – in my rhythm.” Like, there were all these different factors that I had to lead him to that he just couldn’t get to easily on his own. And so I think as long as a boy is swinging between those two places, it’s really hard for him to develop resourcefulness.

Jim: How – how does a mom or a dad minimize that pendulum effect? How – how do you narrow that in? What can you say that will help them cope better and equip them better?

David: I – I do think that empathy and questions formula is really useful in these moments of, “That sounds hard.” Sometimes when – when they’re stuck in blame, it’s, “Tell me what you think your part was in it. What was your contribution?” Or – we laugh. I have a story at the beginning of that chapter about when my sons were 6. And this is an example of how early it starts with boys. We had a soccer game. We’re runnin’ around the house on a Saturday morning. And my son walked up to my wife and said, “What did you do with my soccer cleats?” Like, nothing in him…

(LAUGHTER)

…Thought to say, “Did you see where I left them? Do you have any idea where I put ‘em?” And so in those moments, rather than just, again, coddling – like, I’m gonna go to finding them for him – you know, my wife looked at him and said, “I didn’t wear them. I didn’t wear those with my black skirt.” She was a little playful for a moment. Like, where did you leave ‘em last? Like, helping him move toward some problem-solving on his own as opposed to doing it for him, but not letting him stay stuck in blame.

John: I’m still thinking about the kid, uh, the 11-year-old who struck out. So what kind of counseling can you give that boy to find the answer – not tell him, but to find the answer himself?

David: We spent some time on the front side, just a few minutes, kinda connecting the dots on helping him see where he was swinging from one side or the other. Like, I highlighted for him, like, the two things I’ve heard the most from you are, he couldn’t pitch the ball, and “I’m a loser”. And so we talked a little bit about what those messages are and the two extremes in language that’s doable for him. And then I said, “What are the other possibilities of what could have happened?” And that’s how he got to that place, saying, “Well, I did miss practice once this week and felt like I had an off day ‘cause actually I played a great game on Tuesday.” So he could kind of anchor himself to some truth after a little digging and an exploration.

Jim: That – that is really helpful. I’m – I’m thinking of that just in my own parenting, my own fathering. Those are good things to come back around on. And when you notice them not doing as well, ask those empathetic questions. I like that. Um, Sissy, how ‘bout for the girls? When it comes to resourcefulness, what’s their stumbling block, and what’s the building block for them?

Sissy: I think girls, for any of us, when we come up to a roadblock, resourcefulness is really workin’ our way around it. And I have more and more girls who just sit down by the roadblock. Some of ‘em plant flowers. Some of ‘em draw pictures.

(LAUGHTER)

They don’t even care about getting around it. And…

Jim: Why is it important?

Sissy: Right.

(LAUGHTER)

Why is it important? Yeah. And so motivation is one of the building blocks that we talk a lot about. And I think sometimes we’re imposing our motivation on them rather than helping them find theirs. And so we keep going back to empathy and questions. But I think even in those times – I mean, one of the questions I ask the most in my counseling office is, “What do you want? What do you want to happen here? What do you think, again, is – what do you think’s gonna help?”

Jim: I wanna end with this question and for each of you to answer this because I think – um, you know, you’re doing counseling. You have the techniques of counseling. Uh, these are things that we believe, as Christians, are all rooted in biblical truth. I think we can all agree to that. Why do you think God does it this way? I mean, when you look at the, uh, little years of tryin’ to teach them, and then those hormonal adolescent years, and then puberty hits, and you got the teen years – when you’re looking at the big picture, what does God want from us as a parent – as a father, David, and as a mother, Sissy?

David: I would say I think what He wants most for me as a father is, uh, to be transformed more into the image of His son. And He’s…

Jim: What does that look like?

David: …Gonna use these beings to disrupt me…

(LAUGHTER)

…And take me to the end of myself and help me figure out I’m making more of a mess than I’m doing it well in a lot of moments and that there’s grace for that. And we talk about this in the spiritual milestones of just how we cannot really understand the beauty of grace unless we understand the depths of our need. And so I think that’s what – what it’s about for me, more than anything.

Jim: Sissy, in that mom space, the mom that’s to her wits’ end – she’s so worried. She’s not in control. All the things we’ve talked about these last couple of days, those, um – maybe you might call them the sensitive spots for Eve. You know, where Eve lives, those attributes that so many women, so many moms, possess. How does she wrestle herself away from that and actually trust God, even in the midst of really serious stuff?

Sissy: I would say a lot of dependence, um, just like David talked about, and – and that one of the things I sit with moms and talk about all the time is God gave you exactly what you need already for the life of each of your kids, even the one that’s the most challenging. And that child really, in effect, will be the most transformative and will teach you your need for Jesus and His grace and mercy for you so that you in turn can spill it over to them because that’s so much of what we do when we love kids.

Jim: Boy, so good. And you have done a wonderful job in this book, Are My Kids on Track? The 12 Emotional, Social and Spiritual Milestones Your Child Needs to Reach. I mean, so many parents contacting us here at Focus on the Family are sayin’, “Am I doin’ the right job?” This is one of those resources, these tools that can really enlighten you as to whether you are. And I’ve loved what I’ve heard, David and Sissy. Thank you so much for being here, uh, with us. We so appreciate it.

Sissy: Thank you.

David: Thank you for having us. We’ve loved it.

Jim: And listen, this is why Focus on the Family is here. We want to provide you with biblical answer and trusted advice as you’re raising your children. That’s what we want as we’re raising ours. We have many, many resources available to you like our 7 Traits of Effective Parenting Assessment tool, which really reveals your individual parenting strengths and those things you can work on. It’s worth doing just for that reason. We also have a feelings chart with our beloved Adventures in Odyssey characters and David and Sissy’s book that we talked about today: Are My Kids on Track?

The strength of your family is important to us. We pray for you. And to continue to provide these tools, we need your prayer and financial support to be blunt, especially as we’re closing out our fiscal year. We need to know how to budget for the coming year. We are listener supported. You’re the one who empowers us to take a stand for the family and deliver, hopefully, good solid encouragement and counsel. Won’t you do your ministry – I like saying it this way – do your ministry through the mechanism here at Focus on the Family by contributing to the work here? Together, we will reach people for Christ. And when you give any amount today, as our way of saying thank you, we’ll send a copy of the book we talked about: Are My Kids on Track?

John: Donate and get your copy of that great book at focusonthefamily.com/radio, or call us and we’d be happy to tell you more: 800, the letter A and the word FAMILY.

Next time, on this broadcast, a powerful conversation with Kathi Lipp and Cheri Gregory about how you can identify and end your personal pursuit of perfection.

Teaser:

Cheri Gregory: I was the person who was trying harder and harder and it still wasn’t good enough. I was the A plus, plus, plus student, and there was no joy and there was no sense of satisfaction in it.

End of Teaser

Sissy Goff is Director of Child and Adolescent Counseling at Daystar Counseling Ministries in Nashville, Tenn. She has authored/co-authored nine books including Raising Girls, Intentional Parenting and Taming the Technology Monster. Sissy is a sought-after speaker for parenting and teacher training events around the nation, and a frequent guest and contributor to several media shows and publications. Learn more about Sissy and follow her work at her blog, raisingboysandgirls.com.

Receive the book Are My Kids on Track? for your donation of any amount!

Good parents aren't perfect. And that's okay. There's no formula to follow, but there are ways you can grow every day. This assessment gives parents an honest look at their unique strengths, plus some areas that could use a little help.

A practical Focus on the Family resource that can assist you in helping your kids talk about their emotions. Includes a full-color chart featuring popular Adventures in Odyssey audio drama characters

The emotional health of children in our culture may be declining. Here’s what parents can do.

In this Adventures in Odyssey drama, a carelessly uttered word from Eugene creates havoc as it becomes the fashionable insult, resulting in a lesson about the power of words.

This discussion offers a preview of Volume #16 “Cultures in Conflict” from the That The World May Know video series, available below.

Debra Fileta will help couples better understand the four seasons of healthy relationships, what to expect during each one, and how to carefully navigate them for a stronger marriage. (Part 1 of 2)

Larnelle Harris shares stories about how God redeemed the dysfunctional past of his parents, the many African-American teachers who sacrificed their time and energy to give young men like himself a better future, and how his faithfulness to godly principles gave him greater opportunities and career success than anything else.

Amy Carroll shares how her perfectionism led to her being discontent in her marriage for over a decade, how she learned to find value in who Christ is, not in what she does, and practical ways everyone can accept the messiness of marriage and of life.

Psychologist Dr. Kelly Flanagan discusses the origins of shame, the search for self-worth in all the wrong places, and the importance of extending grace to ourselves. He also explains how parents can help their kids find their own sense of self-worth, belonging and purpose.