It wasn’t an abortion case. It wasn’t a marriage case. But it was a case about where in the Constitution certain fundamental rights of Americans are guaranteed. It was a unanimous opinion. All nine justices agreed that the 14th Amendment provided the answer.

But one justice, who agreed with the final decision, wasn’t satisfied with the majority’s reasoning, and filed a concurring opinion containing different reasoning. Same Amendment, different clause, he argued. Why is that important?

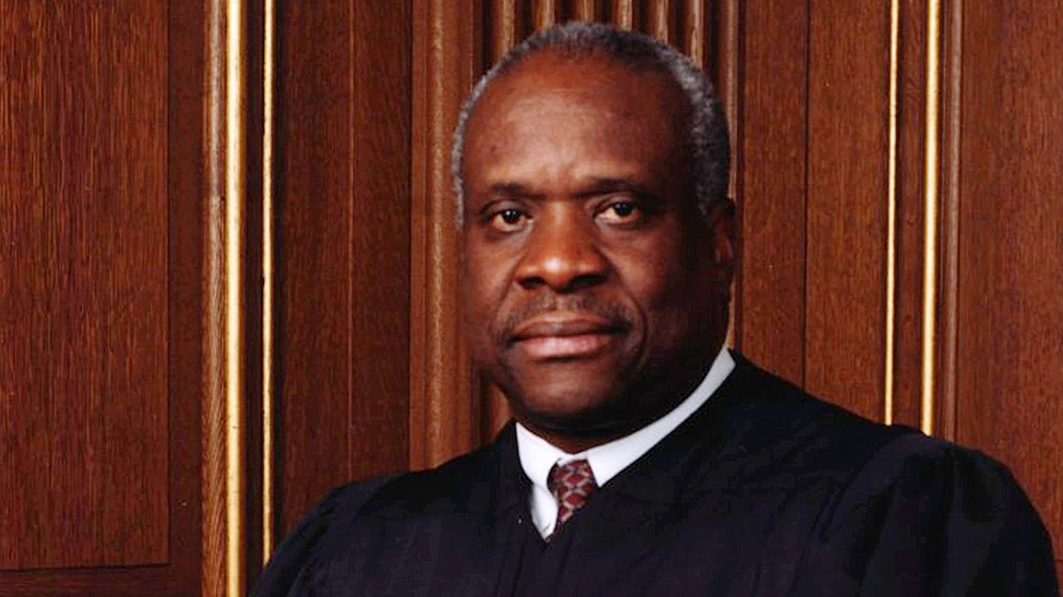

Because, Justice Clarence Thomas noted, the majority was relying on a clause and a misguided interpretation of it that gave us corrupt Supreme Court decisions like Dred Scott v. Sanford, Roe v. Wade, Planned Parenthood v. Casey, and Obergefell v. Hodges.

That’s a huge indictment of the Court by Thomas. And it came in a seemingly unrelated case.

The case, Timbs v. Indiana, involved an issue that pitted citizens, who own property that may have been used to commit a crime, against the government, which in accordance with state law, can seize such property and sell it and keep the proceeds. An important case, constitutionally, but one which, at first glance, doesn’t appear to have much to do with abortion, marriage, or social issues at all.

And yet Thomas called the court to task for using a particular clause of the 14th Amendment, dealing with “due process” (also found in the 5th Amendment), which prohibits any state (or, per the 5th Amendment, the federal government) from “depriv[ing] any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.” The phrase originally meant that government must afford you some type of the notice of charges against you and opportunity to tell your side of the story before it can levy a civil or criminal punishment against you.

Unfortunately, over years and decades of Supreme Court decisions the Court massaged the “due process” clause into a concept dealing not with procedural rights, but with substantive (i.e., fundamental) rights (e.g., the rights of marriage, privacy, speech, travel, vote, religion, freedom of association, etc.) and gave it the oxymoronic title of “substantive due process.” It is a concept that is supposed to protect rights that are so deeply rooted in the nation’s history and tradition that they are deemed to be “fundamental.” The government must have a “compelling interest” for interfering with such fundamental rights, which is a tough legal hurdle to clear.

However, Thomas noted in his concurring opinion that: (1) the Court should be using the “privileges and immunities” clause of the 14th Amendment when identifying fundamental rights, and; (2) because it’s using the wrong clause, sometimes the Court defines the universe of fundamental rights “so broadly as to boarder on meaningless,” citing (and condemning) the 2015 same-sex marriage case of Obergefell v. Hodges, as well as the 1992 abortion case, Planned Parenthood v. Casey.

Thomas then criticized the Court for using substantive due process “without any textual constraints,” (i.e., no limits in the text of the Constitution or anywhere else), and concluded that “it is equally unsurprising that among these precedents are some of the Court’s most notoriously incorrect decisions.” He pointed to two infamous Supreme Court decisions: Roe v. Wade, which decided that abortion is a constitutional “right,” and Dred Scott v. Sanford in which the Court famously held in 1857 that slaves were “property” and therefore could not be American citizens.

Thomas has been a consistent foe of Roe v. Wade while on the Court, and is currently the only justice who is on the record as saying it was decided incorrectly. It was encouraging that Justice Neil Gorsuch, in a separate concurring opinion in Timbs v. Indiana, noted that Thomas was likely correct concerning his criticism of “substantive due process.” That statement alone is an encouraging sign of Justice Gorsuch’s potential stand in any future cases where the holdings of either Roe or Obergefell or any other “substantive due process” claim comes before the Court.