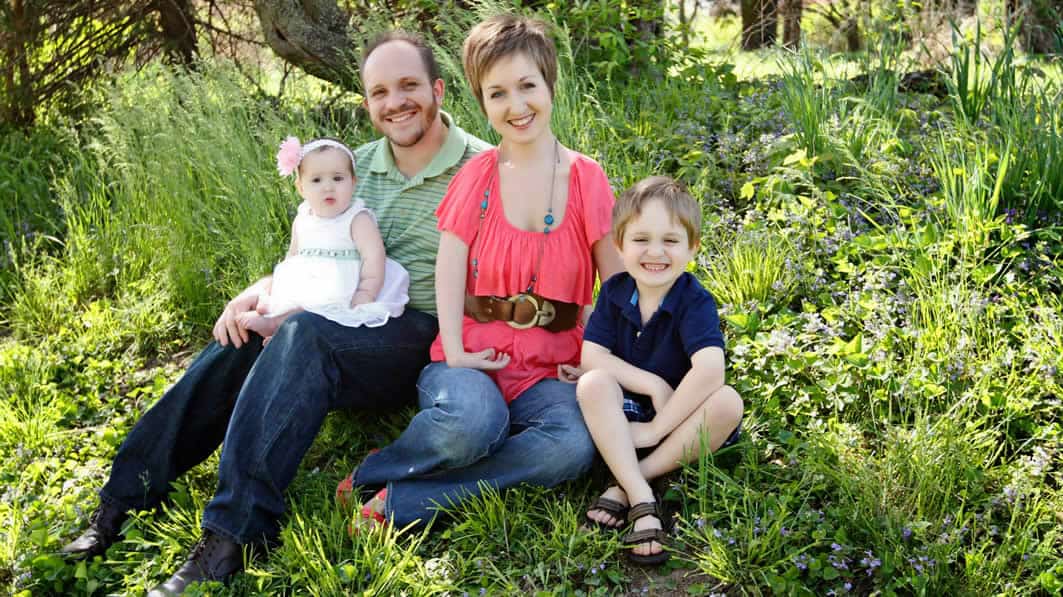

A YouTube video of Sarah Kovac changing her baby’s diaper has been viewed more than 400,000 times. Thousands have also watched clips of her driving, playing the piano, applying makeup and even cracking eggs. Simple, everyday tasks, right?

Not without the use of arms or hands.

Sarah was born with arthrogryposis multiplex congenita, a genetic disorder in which leg or arm joints are essentially stuck in place and muscles don’t develop. For Sarah, those locked joints — and the muscles within those joints — run from the base of her neck to her fingertips.

Beginning at an early age, Sarah learned to rely on her legs and feet to handle the duties of four functioning limbs. Today, those duties include raising a 6-year-old and a 2-year-old. Sarah shares the lessons she’s learned in her 2013 book, In Capable Arms: Living a Life Embraced by Grace.

In the following interview, Sarah addresses topics ranging from the lessons of everyday life to ways parents can raise kids who are sensitive to the differences of others. Through both words and actions, Sarah testifies to the value inherent in every life.

Parents of a child with disabilities might wonder how they, too, can raise their child to have confidence and courage. For example, your own parents dealt with multiple broken bones in your childhood after you fell on your arms, but that didn’t stop them from letting you ride a bike and roller-skate. How did this work?

When I was in kindergarten, I broke my arm four times. My arms don’t bend, they just break. My parents had the strength to watch me go through that over and over and still say, “You can learn to ride a bike. We’ll take off your training wheels.”

I would come across things that I couldn’t do or didn’t want to because it was too scary for me, but they let me discover those things instead of determining them for me.

Many parents have a hard time with this, understandably, because they feel their child won’t develop to his or her full potential. So they intervene. They say to the child, “Maybe you should do it this way, or do this with your mouth, or use your other hand,” and that sort of thing. I cringe a little bit when I see that, because in my experience it was really helpful for my parents to back off and let me find own way.

When you’re a parent of a child with special needs, you have the internet and doctors and therapists who all have different opinions — and all these things are needed — but it’s hard to step back and say, “God, I trust that You’re going to show me what to do. I trust that [my children] will find their fullest potential in You.”

Words often have an impact on a child’s self-esteem. Can you remember examples of words or descriptions your parents used that stuck with you over the years?

I came home from school one day after somebody told me I was handicapped. This was during the 1980s, and that was the word used back then. I’d heard the word before, but I don’t think I’d ever been labeled that way.

So I said something about it to my dad, and he said, “You’re not handicapped. You have a handicap, and there’s a difference.”

I learned that I am Sarah first and foremost, and I also happen to have a disability. I don’t have to let myself be defined by these things. There’s no escaping it, but it doesn’t mean it’s who I am.

I also remember my mother telling me that a good artist can work their mistakes into the bigger picture. I’m not saying that God makes mistakes. … God is the artist and can work anything for good. It’s a comforting thought.

Using your legs and feet to accomplish everyday tasks looks exhausting. How do you do it — especially when it comes to raising your children?

One thing that’s helpful for me is that we all go to bed at the same time, which is 7:30 or 8 p.m. I’m always well rested. I get up at 5 a.m. to make sure I have an hour to myself. The other thing that really helps a lot is that I don’t try to do everything myself, especially with my 6-year-old. He’s a huge help.

When I get him up at 6 a.m., he feeds the pets and puts the dishes away. We almost always have the same breakfast — peanut butter and honey — so he can make it himself if I’m busy with the baby. I find ways to keep him involved and make him part of how the household works. It’s like having a little partner.

You say your 6-year-old son is part of a system that makes the the household work. What kind of person do you hope he’ll be having a mother with special needs?

He is already very nurturing. I don’t ask him to take care of me. He doesn’t have to do much with helping me, but he does notice. If he sees me struggling with a button, he offers to help. He’s a compassionate and sensitive person. He doesn’t hesitate to jump in and help when he thinks someone needs it.

From a young age we’re instructed by parents not to stare at people with physical disabilities, but do we sometimes miss an opportunity to teach children to value those who are different?

I get uncomfortable around people with disabilities, too. I don’t know what their capacity is or how they’d like me to interact. I totally understand what that feels like.

Parents should try to model how to interact with people with disabilities. Strike up a conversation about the weather. Talk to them just like you would with anyone else.

Can you give us an example? Some conversation starters for kids?

“I don’t know why [her hands are like that, she’s in a wheelchair, etc]. God made everyone so different, didn’t He?”

Really drill down to understand what the child thinks about the situation. Then you can effectively encourage a more tolerant approach. For example:

Child: That kid has funny things on his legs!

Parent: Yes, he does. … They’re called braces. What do you think about that?

Child: I think he’s a robot! (I could so hear my son saying that.)

You then can explain what leg braces do, and that they are not like robots — but that some people have prosthetic limbs and those are kind of robot-like. Understand their questions and use them to teach.

“Yes, she is in a wheelchair. And look how cute her shoes are!”

I know this seems like brushing the issue aside, but to a person with a disability, shoe choice is probably more interesting than their adaptive technology. Acknowledge the person’s disability, but then point out something relatable so the kid can connect.

With genetic testing today, many women today know in advance when they’re giving birth to a child with special needs. What would you say to a mother considering abortion in the face of an adverse diagnosis?

Doctors said some terrible things to my parents about what they expected from me and how independent they thought I could possibly be. They gave them a grim prognosis. My biggest fear for them [these women] is that doctors are not always right.

The parents you see who have children with special needs and are making it work are not any different than you. They’re doing what they need to do to love their children the best they can. The parents are not special themselves. They don’t feel adequate and up to the task, but no one does! God takes that situation and grows something special in you. God can even create a community around you to help get you through it.

Finally, in many cases people want to use a label to describe a person with a disability. What do you suggest?

Most of us don’t like “differently-abled,” “diff-ability,” what have you. We are people, first and foremost, and that’s where we’d like the emphasis placed. We are “people with disabilities.” I really appreciate the question.

For more with Sarah Kovac, listen to the Focus on the Family broadcast “Learning to Trust God Through My Disability,” and visit her YouTube channel.