The War of Words

In this Adventures in Odyssey drama, a carelessly uttered word from Eugene creates havoc as it becomes the fashionable insult, resulting in a lesson about the power of words.

Home » Episodes » Focus on the Family Broadcast » Discovering God in the Midst of Pain and Suffering (Part 1 of 2)

Pastor Timothy Keller offers some perspective and hope for those times in life when trouble and hardship cause us to question our faith in God. (Part 1 of 2)

John Fuller: Pastor Tim Keller was once asked why he thought God allowed pain and suffering. And his answer was very candid and refreshingly honest when he said, “I don’t know.”

On this Focus on the Family broadcast, Dr. Keller will help us explore the subject of pain and suffering beyond the “I don’t know” answer. And your host is Focus president and author Jim Daly; I’m John Fuller.

Jim Daly: John, you and I recorded a conversation with Pastor Keller in New York City a while back, on this topic of pain and suffering. Why God allows suffering may be the biggest question that we ask the Lord as Christians because it’s hard to contemplate a good God, then see all the suffering that occurs in the world. But we do know that the Scripture tells us that Jesus was well-acquainted with grief and that He is the Great Comforter. Being in New York City to record with Dr. Keller and being mindful that today is the anniversary of 9/11 – a day in which we saw so much suffering and loss – as a nation, we want to remember those who died that day as well as the courage and the unity that we witnessed.

John: And Tim has lived in New York City – he knows all about that day and how painful it was. And Tim Keller is the founding pastor of Redeemer Presbyterian Church in Manhattan. He’s also the chairman and co-founder of Redeemer City to City which plants new churches around the globe. And he’ll help us deal with the difficult questions today on Focus on the Family.

Jim: Tim, that is uh, really the crux of the Christian life isn’t it? Is how do we – how do we define and discern what suffering does in our lives? Why do you think God allows us to suffer?

Tim Keller: Well, now if you pose the question like that, you know, what does God do with suffering in our lives? There’s lots of good answers to that, lots of good answers. The Bible’s filled with them. Uh, it teaches us patience, teaches us humility. It uh, generally suffering means something that’s valuable to us is threatened or taken away from us.

And uh, Saint Augustine said that our biggest problem is what he would call “disordered loves.” We – we love things too much. Like for example, we may love our comfort. We might love money. We may love even our family – I’m saying this to Focus on the Family – we love our family more than God, so that’s a disordered love.

So, if you – if you love God fourth and your – your family third and your job and money second, you know and your maybe self-esteem and reputation first, that’s a disordered heart. And it creates all kinds of problems, of course. I mean, obviously, if you’re putting money over your family, that’s gonna create problems. If you put what your family – how your family’s doing over what God thinks about you, it creates all sorts of problems. Suffering comes along, usually uh, goes after one of those things that is too important to you…

Jim: Hm.

Tim: …and forces you to turn to God in a way you weren’t before or walk away. I mean, you could just say, “Okay, God’s letting this happen. I’m angry and I’m out.” But what happens is, if you turn to God and say, “I need to rely more on Him than on my wealth, which I’m losing,” or “I need to rely more on Him than my health, which I’m losing,” or “My wisdom, which isn’t working,” it reorders your heart’s loves and makes you a stronger person and it makes you a humbler person, makes a more patient person.

The Bible’s constantly talking about how suffering is a – a refining fire and we’re like the metal ore that goes through, and we come out the other side more pure. So if you asked that question that way – “Why does God let suffering – how does God use suffering in our lives?” There’s lots of great answers to that.

Jim: Is it reasonable to believe that uh, well, God has a purpose in it?

Tim: A purpose that’s over and beyond just making us better people?

Jim: Correct.

Tim: Yes, but that’s what we don’t know. We do not know what that would be, because what that means is – and this is the question I think, put it like this: we know that if we – if God is good, He doesn’t enjoy our suffering. If He’s powerful, He could stop the suffering, but He doesn’t. So if He said He doesn’t enjoy suffering and we know He could stop it, but He doesn’t, then the question is, He must have some purpose for us to be going through the suffering, that has to be good, but we have no idea what that could possibly be. And that’s the reason why, if somebody actually says, “Why does God allow evil and suffering in the sense of, what purpose does He have for allowing evil and suffering to continue?” There the answer’s gotta be, “I do not know. I have no idea.”

Jim: There’s a Scripture that caught my attention in prepping for our discussion today. It’s in 2 Corinthians 4:17, where Paul writes, “Our light and momentary troubles are achieving for us an eternal glory that far outweighs them all.” Does that play into this discussion? What is Paul describing for us there?”

Tim: Yes, but see now that’s got – that goes back again to the fact that suffering does great things in us. And that’s gotta be part of the answer for why suffering and evil happens. Uh, in fact, somebody once pointed out that if there was no evil and suffering, there would never have been such a thing as courage…

Jim: That’s true. You wouldn’t need it.

Tim: …Or sacrifice.

Jim: Right.

Tim: See, you would never have to sacrifice. You wouldn’t have to give your life for someone else. Are we really thinking that sacrifice and courage are, you know, not important things? They’re good things. That certainly doesn’t feel to me, like enough of a reason for God to allow so much of the stuff that’s happening in the world. But you can begin to get a sense of “Okay, so because of evil and trouble, uh, there’s such a thing as sacrifice, such a thing as courage. People’s lives very often – people find God because of suffering. People grow into Christlikeness through suffering.” You can start to see some reasons. They’re not sufficient. Uh, but in the end, every time I try to make a long enough list of things I see God doing through suffering, does this justify Him allowing the horrendous pain that we see? No. There’s gotta be more reasons that we just don’t know about.

Jim: Yeah.

Tim: And that’s the reason why we have to, in the end, say, “I don’t know.”

Jim: Does that also tie into to where Paul wrote uh, in terms of suffering leads to perseverance, perseverance – character and character – hope? I think I get the first three of those. I’m tryin’ to better understand how those three parlay into hope.

Tim: Oh.

Jim: Why do those three things give us hope?

Tim: Well, see, when you go back to Saint Augustine, which I was talking about before, when Augustine talks about – he thinks the core of who we are is what we love. The difference from the city of God and the city of man is the city of God is the community of people who say, “God is my highest love. God is what I love.” The city of man is power, self. “That’s what I love. I love power for myself, wealth for myself, prosperity for myself, not God.” But when – see, when he’s talkin’ about love, he doesn’t just mean what we think, which is sort of emotional affection. He’s also talking about what do you hope in?

Jim: Hm.

Tim: What do you rest in? What do you depend on? What do you look to for your significance and security? And so, it’s not that hard for me to see that if I love, for example, my job and I put too much hope in my talent, my smarts, my ability to figure things out, because I got into the right grad school and I got this great job and now I’m making a lot of money and I think I can buy another – buy two homes and I’ve put all my hope in my own wisdom and my discipline and my talent. And I’m also putting hope in prosperity and the material things, and along something comes and my career is ruined. Somebody betrays me. I have an injury and I can’t do something – suffering. I’m gonna have to put my hope in God in a way I was putting hope in myself, or having to love God more than I love my – my own wisdom. And so, hope and love, I think in the Augustinian sense are similar. It’s what you – it’s what your heart rests in.

Jim: It’s where you find peace.

Tim: Yeah, yeah, so that – I’ve no problem with seeing how suffering leads to hope – hope in God.

Jim: In that context, too, in the Western culture particularly, as we’re talking about what we yearn for as human beings, which is usually comfort and ease…

Tim: Yeah.

Jim: …How does that play into even our Christian understanding as a Western Christian? We tend to not want to suffer. We don’t think that’s good. In fact, we’ll build theologies…

Tim: Right.

Jim: …around not suffering.

Tim: Right. Well in the book, Walking With God Through Pain and Suffering, there’s a – his name is escaping me – a doctor who spent about half of his career in India. He was a British doctor – about half his career in India treating many, many poor people and then about half his career in America. And he says – he says, “Western people just cannot handle suffering in a way that non-Western people – non-Western people are far better at taking it, far better. They expect it. Uh, they’re way better at taking it. Western people melt down. They feel like it’s not right. It’s not fair. They really can’t handle it.”

And see, that’s why I think it’s fair to say that up until about 500 years ago, most people in the West didn’t know why God allowed evil and suffering, but they didn’t expect that they should know. They figured, “Of course it would be a mystery. Of course, God is bigger than me. Of course, life is, you know, swift and brutish, and then you die and you go to Heaven. And of course, there’s gonna be suffering here and we don’t understand why, but that’s all right. I mean, it doesn’t mean there’s no God.”

Today people feel like, “God owes me an explanation and if I’m living a pretty good life, God owes me a good life. That’s called – Christian Smith calls that “moralistic therapeutic deism”…

Jim: Hm.

Tim: …That if you – our assumptions are that if there is a God, it’s His job to give me a good life as long as I live a – live according to my standards.

Jim: How…

Tim: And so that’s why…

Jim: Yeah.

Tim: …the problem of pain is a bigger deal to us now and a bigger deal in the West than it has been other places in the world or in the past.

Jim: And you talk about that transformation of that thought. Explain why. Why did we used to understand it…

Tim: Oh.

Jim: …and today we don’t? Is it the power of media? Is it what we…

Tim: No.

Jim: …learn to expect and embrace?

Tim: It’s a deeper than that.

Jim: What is it?

Tim: Well, it’s deeper than that. It’s our idea that um, in the book – in my book on Walking with God Through Pain and Suffering, I – I look at Charles Taylor, who wrote a book called A Secular Age in which he tries to – he’s a Canadian philosopher, and he tries to explain this shift.

Jim: Mmhmm.

Tim: Part of the shift is that a different understanding of the self – that we have today the idea that the self has to be able to determine right and wrong. We don’t align with meaning out there. We create our own meaning. The self also because of our reason, we – we can figure things out. In the past, there was much more of a sense that the world is filled with mystery and our reason can only go so far. There was humility before the universe. Um, modern times, we actually believe that the world is a – an imminent order of natural causes, that everything’s got a natural explanation. Everything’s got a scientific explanation. If we figure this out, we can pretty much make the world the way we ought – it oughta be. And we don’t have that humility before the mystery anymore. So, that’s – that’s a major shift. It’s so deep that people don’t even see it. It’s like…

Jim: Hm.

Tim: …Cultures – invisible to the members of the culture, you know. And this inflated view of the self and its ability to figure things out is something that everybody takes for granted now. But that’s the reason why up until the Lisbon earthquake like in the 1700’s and then a lot of the philosophers started to say, “Well, how can we believe in a God who lets this happen?” There have been earthquakes for centuries…

Jim: Sure.

Tim: …Before that and people believed in God and it – they said, “Wow, this is awful,” but – and Job, you know, was mad, but he didn’t say, “You can’t exist.” And today, unless God answers to us and give a good reason for pain and suffering and we don’t have one, a lot of people say, “That gives me a warrant for walking away from Him.”

Jim: I mean, that’s a profound statement and I think an accurate one, that people use that now as an excuse…

Tim: Mmhmm.

Jim: …To not engage God because He didn’t treat me right.

Tim: Right. One of the things that I love about Job and I learned this many years ago when I was at Gordon-Conwell Seminary and I had a – a professor of Old Testament explain that for many years he read the book of Job and during the book you see Job, because he’s suffering, he’s crying out. He’s cursing the day he was born. He’s actually saying to God, “If You would appear to me, I have a bunch of questions for You. And I don’t know, you know, how You’d answer them.” And he talks very uh, what we would consider pretty disrespectfully at some points to God.

At the end of the book, God shows up and essentially says, “Job, you have handled things rightly.” And he’s mad at his friends and says, “If Job prays for you, maybe I won’t punish you.” So at the end of the book, He shows up and basically vindicates Job. And yet, if you go back through the book, it looks like Job – looks like he blew it to me. And – and then here’s what the Old Testament professor said. “He never stopped praying.” He was complaining and he was yelling and he was screaming and he was biting the rug, but he always did it in God’s presence. He never walked away.

Jim: Hm.

Tim: He was processing it through prayer. He never ever even hinted that God didn’t exist or that there was any possibility of him living without God.

Jim: And that’s a good uh, thing to remember when we are struggling through something. God doesn’t mind you being honest with Him. In fact, He wants you to be.

Tim: That’s exactly the right balance you get from the book of Job. He – you can be far more honest than we usually are – read Job.

Jim: Yeah.

Tim: I love the place where it – early in the book it says uh, Job shaved his head, tore his clothes, shrieked, fell to the ground. And it says, “In all these things, Job sinned not.” And I think in the average Evangelical church, we would say, “Oh, that poor guy. He lost the victory.”

Jim: Right.

Tim: You know, if he was real, he’d be praisin’ the Lord and just trustin’ the Lord. He wouldn’t be doing all that.

Jim: Well, and it shows God loves an honest heart most of all.

Tim: Exactly. In fact, the Psalms are filled with complaining – complaint prayers.

Jim: Let me ask you, when you look at the totality of Scripture um, and for those that have read the Bible all the way through, a great deal of it does point toward pain and suffering, doesn’t it?

Tim: Oh, my word, you could actually say the whole Book’s about it, because it climaxes, you know, in the suffering of Jesus…

Jim: Right.

Tim: …Who comes not in strength, but in weakness, Who’s rejected, Who’s – yes. So you really could say practically, the entire Book’s about pain and suffering.

Jim: You know, as we talk about the family – so often at Focus on the Family, we’re receiving um, you know, context through digital media or whatever, where families are suffering. Parents have very high expectations – perhaps they accepted the Lord as teenagers or younger, they’ve lived a pretty good life, they’ve probably have gone through some suffering, but they relied upon the Lord – but then they have that prodigal, that child.

Tim: Yeah, and that can be worse.

Jim: And they – they – yeah, they’re struggling with it. Speak to that environment where the suffering is what you see in perhaps one of your children because they’re not walking with the Lord, or they’re turning their back in a very aggressive way.

Tim: Right.

Jim: How do we not lift up family as an idol in that regard? How do we approach the throne?

Tim: Prosecution is leading the witness here. You’re right, and you’re indicating the right answer I think. I have not had a prodigal. I raised three sons, and yet, of course, anybody who’s a parent – even if you’re not experienced in that – you can just – it just takes a little bit of imagination and you realize the horror of that. And of course, plenty of my friends and parishioners have. And I’ve had people say, “I wish my – I would be happier if my child was dead, than – you know, it’d be better if he’d been killed in a car accident than to be living the way he or she is now. I mean, I’ve heard people say that more than once. So yes, that’s…

Jim: Breaks your heart.

Tim: …That’s suffering, yeah. I do think that there’s a difference between intolerable sorrow that’s aggravated by idolatry and barely-survivable sorrow that happens when you really um, turn to God and say, “You know, You’re my hope, not my children.” And not – there’s no doubt that your – a lot of our self-esteem is bound up in how our children are doing. There’s no doubt about that. We need to admit, if we’re good parents, to what degree? The fact that we’re good parents is a – probably too big a part of our self-esteem. And you’re saying, “No, no, I’m a child of the King, and I’m accepted in Jesus. And my real identity is being a Christian man or woman.” But actually, we get tremendous pride from the fact that our kids are doing well. We are proud of our children both in good and bad ways. And when the child lets us down, it makes us look ugly, makes us look like we’re bad parents, it’s just – we’re ashamed of it. We’re ashamed.

And so, I’d say that even where there is rightful guilt, which is to say, “Here’s places where I did wrong. I repent. I could’ve been a better parent.” But there’s that kind of deep inconsolable shame that I think comes from having made the child more important to your self-image than Jesus Himself. And what you have to do is you have to wrestle with that, and you’ve got to wrestle yourself into greater hope in Christ. And that can salt the wound so that it doesn’t go as bad. It doesn’t mean that it’s not a wound – the rest of your life if the child never turns back. So I’m being realistic about the ongoing pain of that. But I also do think that you shouldn’t necessarily reconcile yourself to all of it. ‘Cause a lot of it probably could be refined and lessened if you turned to God in a new way.

Jim: Yeah, and that deep suffering – it’s something, again, as we’re talking about pain and suffering with Dr. Tim Keller – that’s just something we need to remember, that it often happens in the family. That’s where a lot of that pain and suffering occurs. In fact, although you didn’t have, uh, prodigal children, your suffering came in a physical way from what I understand. How did suffering show up in your life?

Tim: Look, I believe – my wife and I believe that we um, have had garden-variety normal suffering so far. I’m in my – we’re in our early 60’s. Um, my wife’s had Crohn’s disease, and she lost most of her colon with all the inconvenience and difficulties that go with that.

I had uh, thyroid cancer. We worried about that. Looks like it’s cured. But honestly, you know, compared to a lot of – I’ve had other people walk up to me and say, “I’m a cancer survivor, too.” And you – they’ve lost, you know, big parts of their body or – and they have five years to live maybe. And I don’t feel like it’s fair for them to say we’re like, each other. I mean, in other words, my suffering is normal.

Jim: Right.

Tim: And I’m sure there’ll be more. I mean, it has to be more. I’m probably not gonna be, you know, I may outlive part of my immediate family, you know. It’s very, very likely. So, I think the kind of suffering I will experience will be – it’s in the middle. I have not had a charmed life. On the other hand, I try to be careful in the book not to tell people, “I know just how you’re feeling,” because if you had a child die in a car accident or there’s all sorts of far worse things than I went through. But that’s my mild experience of suffering.

Jim: But the point of it, you still have gone through things.

Tim: Yeah.

Jim: And that’s important to note.

Tim: Yeah, I don’t know many people at my age that haven’t already, and eventually, it gets worse. It just keeps getting worse.

Jim: You write about…

Tim: What a nice radio show.

Jim: Yeah.

(LAUGHTER)

Tim: Make everybody feel good.

Jim: It keeps getting worse.

John: Good encouragement for everybody today.

Tim: Everybody feel good.

Jim: The – the Christian path.

Tim: Yeah.

Jim: But there’s glory beyond this; that’s what matters.

Tim: Oh, yes, infinite.

Jim: You write about the fiery furnace uh, in life. What do you mean by it? I was thinking of that riding over here. I’m thinking, “The fiery furnace.” To a point when you leave something in a furnace too long, it gets totally burned up.

Tim: Mmhmm.

Jim: Uh, I think my boys would attest to the fact that if we cook pizza too long in the microwave, it’s gone.

Tim: Yeah.

Jim: Um, what’s the difference? What’s “fiery furnace” in terms of our human experience, our human suffering? Does God put us in there just enough to kiln us in a way that we’re better?

Tim: Sure.

Jim: Or if we’re in there too long, do we die from it?

Tim: Well…

Jim: Can you die from pain and suffering?

Tim: Well, let’s see, if – I don’t want to start mixing a metaphor, but um, 1 Peter does talk pretty clearly about troubles and trials are a fire that we’re plunged into, and our faith redounds with greater purity. So it must be that God is the refiner and the fire is the suffering that’s part of His plan for us. And therefore, 1 Corinthians 10:13 actually says, “There’s no temptation that comes that is more than you can bear.” So that probably must mean that the fire isn’t so hot that it will fry you.

Jim: Right.

Tim: He knows what you can take. So it’s gotta mean that. But if you want to mix the metaphors, you know, I’ve been in the dentist chair or the – you know, or in the doctor’s chair where he says now, “I’m gonna snip this off, but be very still.” And I mean, if I would suddenly start…

Jim: Yeah.

Tim: …Jerking around in fear, he would wound me. So there may be a sense in which when suffering comes, I have to say as a pastor, God knows what you can take, but honestly, I do think you’ve got some responsibility here. This could make you worse as a person or it could make you better. And you need to be patient with it and you need to be following God in this and not you know, not trying to get into behavior that – that medicates. You know – I mean, people, when they go through suffering, very often will get into drink or drugs or get into pornography, anything to kinda just make themselves feel better.

Jim: Let me ask you that. Um, let’s go a little deeper. What does that mean to use those things to medicate? What is the human being that’s caught in those vices, what are they really doing? What does it mean to medicate with those things?

Tim: Well, in that case, it’s a real obvious God substitute. I’m gonna turn to this, rather than you know – false intimacy, which is one of the ways people talk about pornography, as opposed to real intimacy with God, in order to comfort myself.

Jim: What do you think ultimately drives a person there?

Tim: Um, I may be wrong on this, ‘cause I’m not a trained counselor and I – though after 40 years in the ministry, I’ve done a lot of counseling.

Jim: You probably have more training than most.

Tim: But I mean, I would – I – generally it usually means going back to some habit they had before.

Jim: Mmhmm.

Tim: It – I guess that’s not totally true. I’m – I guess I have known some people whose suffering drove them into something they’ve never done before. But by and large, it’s a little bit like, if you um, an illustration I got years ago is um, here’s a bridge. And there may be stress fractures in the bridge itself. In other words, it’s already weak. A truck comes over that’s too heavy and it collapses, not because the truck actually created all those – those flaws, but the flaws were already there and the truck kind of aggravated them.

Jim: Mmhmm.

Tim: So generally speaking, I think uh, places where we have self-pity, places where we – suffering can bring out the worst in you, what it can do is it can actually take small flaws of character that have not been out of control and make them a lot worse, including the self-pity, including the desire to escape instead of face things.

Jim: Right.

Tim: So generally speaking, I think it makes – it takes things we already had wrong with us and brings them out, which gives you another opportunity to grow ‘cause it brings out the very worst in you and you can see a lot of your flaws that you were in denial about.

John: Dr. Tim Keller on today’s Focus on the Family was recorded in New York City talking about pain and suffering and what it means to be a follower of Christ. And Jim, I really appreciate his honesty and the thought-provoking comments he’s offered us today about a very difficult subject.

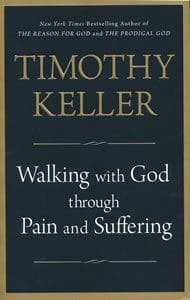

Jim: John, I think he’s one of the foremost theologians and thinkers of our time. He’s written some incredible books, including Walking With God Through Pain and Suffering, which we’re offering today. I’m telling ya, his books challenge you to go deeper in Christ. In this discussion, Tim has done a wonderful job of helping us work through the issue of suffering. And I’m sure we have people listening today who are hurting. You’re looking for encouragement. If you’re in that spot and you need help, please contact us because we’re here for you.

Let me share a story of a listener who did just that. Liz called us after hearing one of our broadcasts on child sexual abuse. She had been hiding the shame that she had felt for a very long time after the abuse happened. And Focus was there for her in very tangible way to bring her healing right from the Lord.

John: Yeah, we hear from folks who are really struggling, who are dealing with marriage and parenting issues. They don’t know who to talk to, and what a privilege to be there for Liz and for all those who call. We’ll encourage you. If you’ve got a trouble that is not going away – it’s really um, just very difficult to process it, give us a call. Make an appointment to have a conversation with one of our Christian counselors as a starting point.

Jim: Also, when you pray and give to Focus on the Family, you’re part of the work that God is doing here; to meet people who are hurting, who have that point of need that you’re referring to, John. You may not think that your gift of ten, twenty, or maybe fifty dollars will go far, but with tens of thousands of folks providing a gift on a monthly basis like that, there’s so much that can be accomplished through Focus on the Family, together. So let me encourage you to make a donation today and do ministry with us. And when you do that, you’re directly impacting people like Liz. In fact, when you support the work of Focus on the Family with a monthly pledge of any amount, we want to say thank you by sending you a copy of Tim Keller’s book, Walking With God Through Pain and Suffering. So, if you can, do it today. Support the ministry, and if you’re only able to make a one-time gift, we’ll still be happy to send you a copy of Dr. Keller’s book.

John: Mmhmm. Yeah, we would. And as you’ve heard from Tim Keller today, there’s so much depth and wisdom he offers on this topic. This is an excellent book to think through the topic of suffering, and we want to put it in your hands, as Jim said – Walking With God Through Pain and Suffering – as our thank you when you donate today.

Our number is 800, the letter A and the word FAMILY, 800-232-6459, or stop by the website, make a donation, get the book and a CD and free download of this 2-day broadcast – that’s focusonthefamily.com/radio.

On behalf of Jim Daly and the entire team, thanks for listening today to Focus on the Family. I’m John Fuller, inviting you back next time for more with Dr. Tim Keller as we once again, help you and your family thrive in Christ.

Timothy Keller was the founding pastor of Redeemer Presbyterian Church in Manhattan, with his wife, Kathy, and their three sons. He was also the chairman of Redeemer City to City, which plants new churches in New York and other cities around the world and publishes resources for faith in an urban culture. Timothy was a New York Times best-selling author whose books include The Reason for God, The Prodigal God and Prayer: Experiencing Awe and Intimacy With God. Timothy went home to be with the Lord on May 19, 2023, after making a tremendous impact for the kingdom of God. Learn more about Timothy by visiting his website, www.timothykeller.com.

Receive the book Walking With God Through Pain and Suffering for your donation of any amount. Plus, receive member-exclusive benefits when you make a recurring gift today. Your monthly support helps families thrive.

In this Adventures in Odyssey drama, a carelessly uttered word from Eugene creates havoc as it becomes the fashionable insult, resulting in a lesson about the power of words.

This discussion offers a preview of Volume #16 “Cultures in Conflict” from the That The World May Know video series, available below.

Debra Fileta will help couples better understand the four seasons of healthy relationships, what to expect during each one, and how to carefully navigate them for a stronger marriage. (Part 1 of 2)

Amy Carroll shares how her perfectionism led to her being discontent in her marriage for over a decade, how she learned to find value in who Christ is, not in what she does, and practical ways everyone can accept the messiness of marriage and of life.

Offering encouragement found in her book Unseen: The Gift of Being Hidden in a World That Loves to be Noticed, Sara Hagerty describes how we can experience God in ordinary, everyday moments, and how we can find our identity in Him apart from what we do.

Rodney Bullard, Vice President of Community Affairs at Chick-fil-A, encourages listeners to make a heroic impact on the world in an inspiring discussion based on his book, Heroes Wanted: Why the World Needs You to Live Your Heart Out.