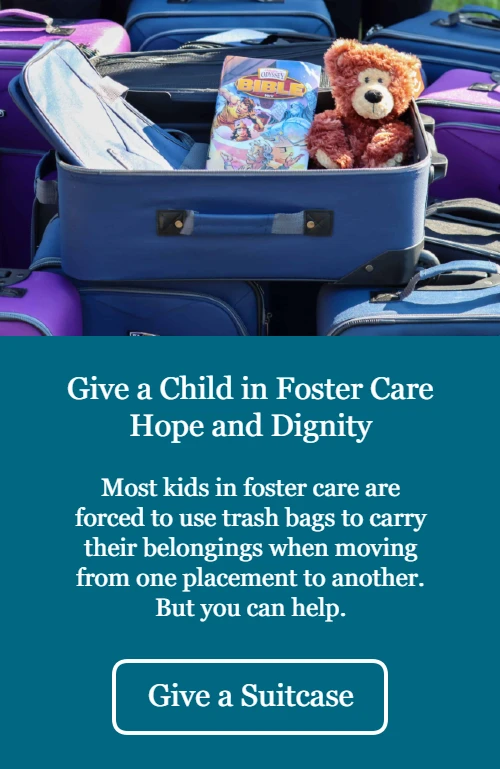

Kevin had always known he was adopted. When he was 18 months old, he had entered foster care because his mother had died from an undisclosed illness, and his father, in distress, left him with a neighbor and never came back. That was the story he grew up with, shared by his adoptive parents.

The problem was the story he believed wasn’t the truth. His parents knew but didn’t want to hurt him or retraumatize him with the true story. Another problem was that everyone else in the family knew the truth as well. At a family picnic, a cousin shattered his heart when she shared the actual story.

That afternoon Kevin learned the truth about his birth parents. His mother did not die from an undisclosed illness. She died a drug addict, and his father did not leave, not voluntarily anyway; he was in prison. Imagine the hurt and anger that Jonathan probably felt. The sense of betrayal was overwhelming. What else has my family kept from me? The foundation of trust crumbled in one day.

The adults in the lives of children growing up in foster care and adoption are genuinely in charge of keeping ahold of their children’s stories to the degree they can. We are the ones that have access to critical information that will help a child grow up with an understanding of his life story, or as Dr. Daniel Siegal says, a coherent life narrative. So, what principles should we follow?

Principles for Telling the Truth*

1. Initiate conversation about the child’s life story.

Children are not solely responsible for asking; parents and caregivers are responsible for telling. Children often believe they are being disloyal to the adoptive family when they have feelings and questions about the birth family. As a result, they may avoid conversation about the adoption and the birth family, even when they have burdensome questions or troubling feelings. Ways to initiate a conversation include things like reading an age-appropriate book, bringing up the subject of adoption on a birthday or Mother/Father’s Day. Merely taking a drive together and asking intentional, sensitive questions provides an opportunity that allows the child to share their feelings about their adoption.

2. Do not lie! Under no circumstances should a caregiver/parent lie to a child.

Painting an inaccurate picture of a child’s birth parents or history can generate serious trust fissures. The truth can be revealed, as in Kevin’s case, with a casual remark by either the adoptive parent or extended family or by an accidental discovery of adoption-related documents. In the future, a teen may discover truths through social media or in search and reunion. If this happens, a rift in the parent/child relationship occurs—a fracture that is difficult to repair with an apology or explanation. What began as “protection” of the relationship with the adopted child can become a “termination” of trust and intimacy in that relationship.

3. Tell information in a developmentally appropriate way.

A young child cannot possibly understand difficult information, but this information can be shared as the child grows, and asks for more details. Share all information by the time the child is 12 (developmentally). This age is an excellent time to share all facts for several reasons. Primarily, most children at age 12 are just beginning to think more abstractly and can receive this information. Disclosing the story age-appropriately risks accidental disclosure.

4. Remember, the child knows more than you think.

It is essential to know, specifically for older adopted children, what the abuse or neglect was—because it happened to them. They were there when it happened. We should talk about life experiences they lived through. They may have been pre-verbal when it happened, but that does not mean they do not remember. They have deep emotional memories and need words to explain what happened to them. Children learn early on from the open or closed communication environment just how they are to handle sensitive issues—whether to tiptoe around them or deal with them directly.

5. Don’t impose value judgments.

A caregiver may think a piece of information is devastating; however, it may be the key to the child’s understanding of why he or she is living in a children’s home or in foster care. Information about a child’s history may seem very negative, even horrific, to caregivers/parents or social workers, but may be interpreted quite differently by the child. Information about a child’s history should never be changed or given to an older child with significant omissions. Facts must be presented, however, without the overlay of values and judgment. Adults should share hard truths with compassion toward the child who may have been neglected, abused, or abandoned.

An Additional Word

Don’t forget; it is the child’s story. The history belongs to the child, not to the adoptive parents. If friends or extended family members ask about sensitive information, tell them the information belongs to the child. Encourage family members to wait until the child is old enough to decide what questions he wants to answer.

Parents/caregivers may want to assist the child in developing a short, simple version of his or her story that they feel comfortable sharing with neighbors, school friends and teachers, relatives, and other acquaintances. This “cover story” may be very similar to the information given to your child when he was very young. Let the child know that he does not withhold information from acquaintances because it is shameful, but because he should not have to explain his history in all its detail to anyone and everyone.

The Final Principle:

Walking in truth sets everyone free.